What follows is a paean to the artist studio, a place like no other in our contemporary culture. Here I am less interested in the art being made than the setting itself that enables all that making. An artist’s studio is more than mere raw space but a uniquely situated, psychological space where creative insights are more likely to emerge (than, say, in the TV room). The “Calling” of the title is an exhortation to artists to push their work beyond mere “production” and recirculated ideas and imagery. I invoke the ancient Celtic notion of Thin Space as an explanatory metaphor that helps to conceive of the studio as a place of intersections, an interface between the mundane and the unordinary, the actual and the possible.

It is a safe bet that the vast majority of artists view their studios as exceptional places, as pockets of space qualitatively different from any other they inhabit in their day-to-day lives. From a sizable loft to the corner of a bedroom, most artists experience their studio, if nothing else, as a place of solace in a stressful world decidedly short on enchantment.

I am one of those artists, and lately I’m becoming especially fascinated with artists’ relationships with their “exceptional places.” At the time of this writing, I was experiencing a game of musical studios, having moved out of my studio of fifteen years, temporarily operating in a lightless matchbox space while a nicer one was being built. All good in the end, but in the meantime this lurching from studio to studio had me probing my deeper psychological investment in these places.

So what is it about artist studios that so often elicit hyperbolic adjectives such as “spiritual,” “magical,” or “mystical?” All this even though the vast majority of artists (myself included!) spend much of their studio time struggling with pervasive bouts of frustration and creative dead-ends.

Anne Berlit: Essen, Germany

It should go without saying that most complex realities—especially those involving humans—are open to multiple levels of description. On a more quotidian level, artist studios can be viewed simply as workshops where stuff gets made (paintings, sculptures, videos, writings, etc.). Materials go in, labor gets done, and products go out. On a more superficial level, the workshop analogy holds. Similar to workshops of all kinds, art studios are often high-functioning spaces, well-optimized to extract the most storage and functional flexibility from a limited amount of space. And yet the workshop analogy fails to account for more nuanced, psychological dynamics at play. If nothing else, it fails to distinguish art studios from “commercial” workshops by not specifying what the two are ultimately for. Safe to say that the purpose of most conventional workshops is to extract profit, pure and simple. Indeed, for those few commercially successful artists, the workshop analogy is more apt, especially if it is well-stocked with “assistants.” But not so for the vast majority of artists for whom the costs of maintaining their studios far surpass what they gain in sales and commissions.

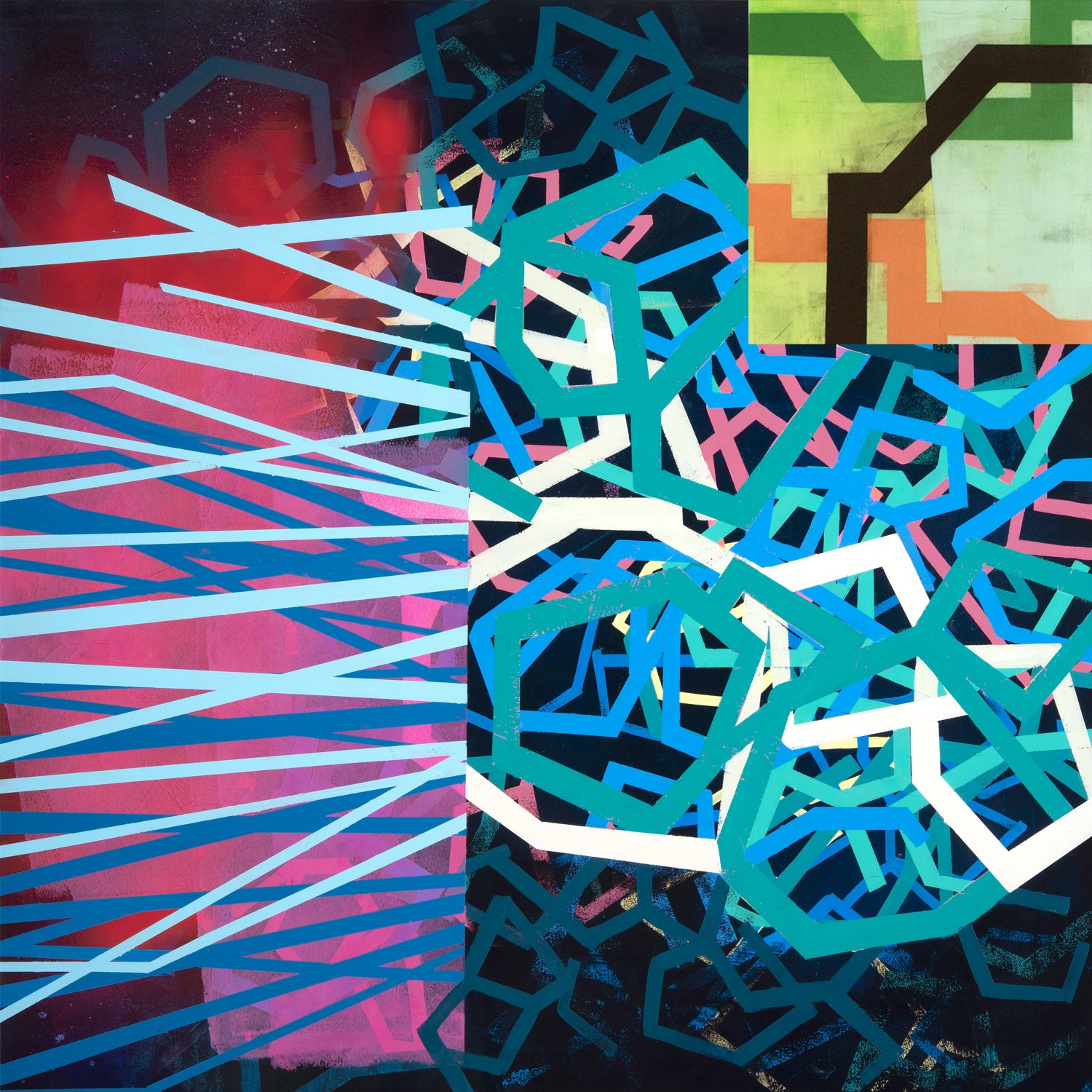

Jennifer Baker: Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

By lingering on the workshop-art studio comparison I’m trying to drill down on the studio experience by articulating what it is not. So along with the crucial difference as to what the two kinds of spaces are for, I’m claiming an even more consequential difference lies in the nature of the labor taking place within them. Let’s face it, from a strictly economic perspective, a good deal of this labor in the art studio is pretty close to worthless.

But viewed from another perspective all that uncompensated effort is worth a great deal to somebody. “Labor of love” is a decent way to characterize this curious kind of toil, but I am interested in what that actually means, and even more, what might be driving so many artists into their studios instead of their TV room. In what follows, I’m speculating on just one among many possible felt (although not easily articulated) experiences that may be playing out in some of these “exceptional places.”

To this end I am turning to the ancient notion of Thin Spaces, which I feel stands as a perfect analog for various kinds of heightened experiences potentially available in the studio. Thin Space is a concept associated with pre-Christian Celtic culture and refers to special places where the boundary between physical and otherworldly realms seemed less distinct and more permeable.These were sacred sites, often pilgrim destinations. Modern day anthropologists have described them as liminal spaces, a term first coined by Arnold van Gennep in his 1909 study, Les Rites de Passage. Here, liminality refers to the transitional stages inherent in challenging psychological or spiritual (and I argue, creative) processes. Other key descriptors especially relevant for this discussion are in-between spaces, or in more contemporary jargon, interfaces. Whether we are talking about the mystical realms of the ancient Celts or the more worldly space of a studio, I am suggesting that both share these core features.

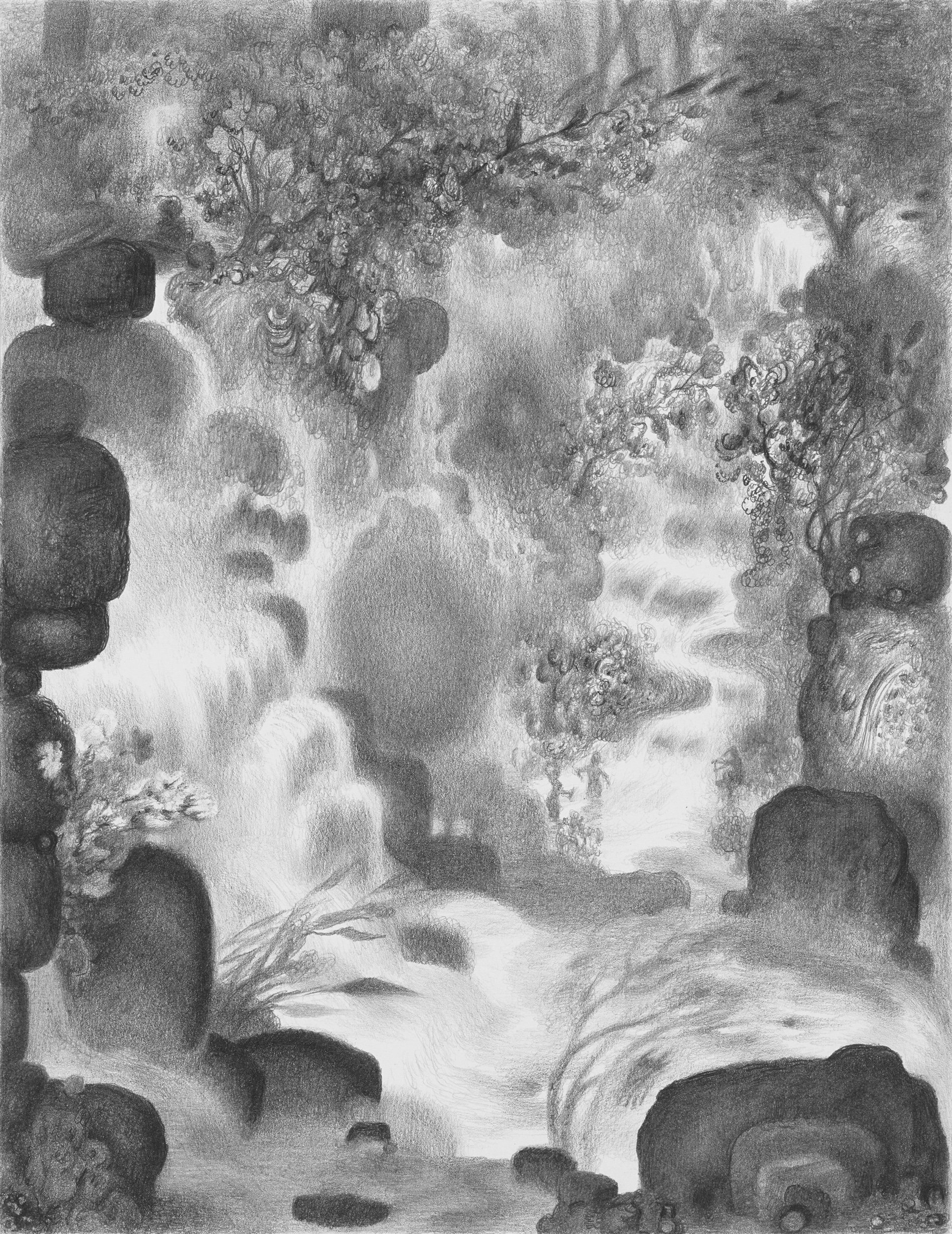

Taney Roniger: Meredith, New York

It seems to me that what lies on one side of our metaphorical interface is the actual day-to-day world, and on the other side, the availability of possible worlds—genuinely new and original ideas, feelings, or insights that one might not only envision but actualize in any number of mediums. So how might artists fruitfully avail themselves of these Thin Spaces where possible worlds are, well, more possible? Let’s put a pin on that for now but, first, two caveats: One, I am not suggesting that all or even the majority of artists would relate to what I am describing, as there are a wide range of motivations for being an artist. Nor am I claiming that artist studios are the only settings that might afford these kinds of experiences. I am focusing on them, because, one, I am an artist and, two, because the wider public has often romanticized the artist studio as a paradigmatic site of transformation (along with numerous other fantasy projections).

So rephrasing the above question, how might artists break through the fog of their humdrum lives to engage the unordinary? It starts by sloughing off one state of mind for another—one more rigid for one more flexible. When an artist walks into their studio they are simultaneously walking away from their mundane world of work and routine, and so it is this literal and metaphorical door that might lead to novel insights and experiences.

Of course, the studio itself is not the agent making this happen but rather the psychological setting that enables it. And it is not just the constraints of the everyday that fall away, but I believe more crucially in our historical moment, it is the algorithmic self (a term first coined by Frank A Pasquale, 2015). Here I am referring to the contemporary self whose very identity and desires are increasingly infilled by digital echo chambers of recirculated imagery and ideas. To be sure, this is becoming a menace to everyone, but to an artist, it’s a looming catastrophe. So to whatever extent the artist can quiet the networked self, genuine creative breakthroughs are more likely to follow.

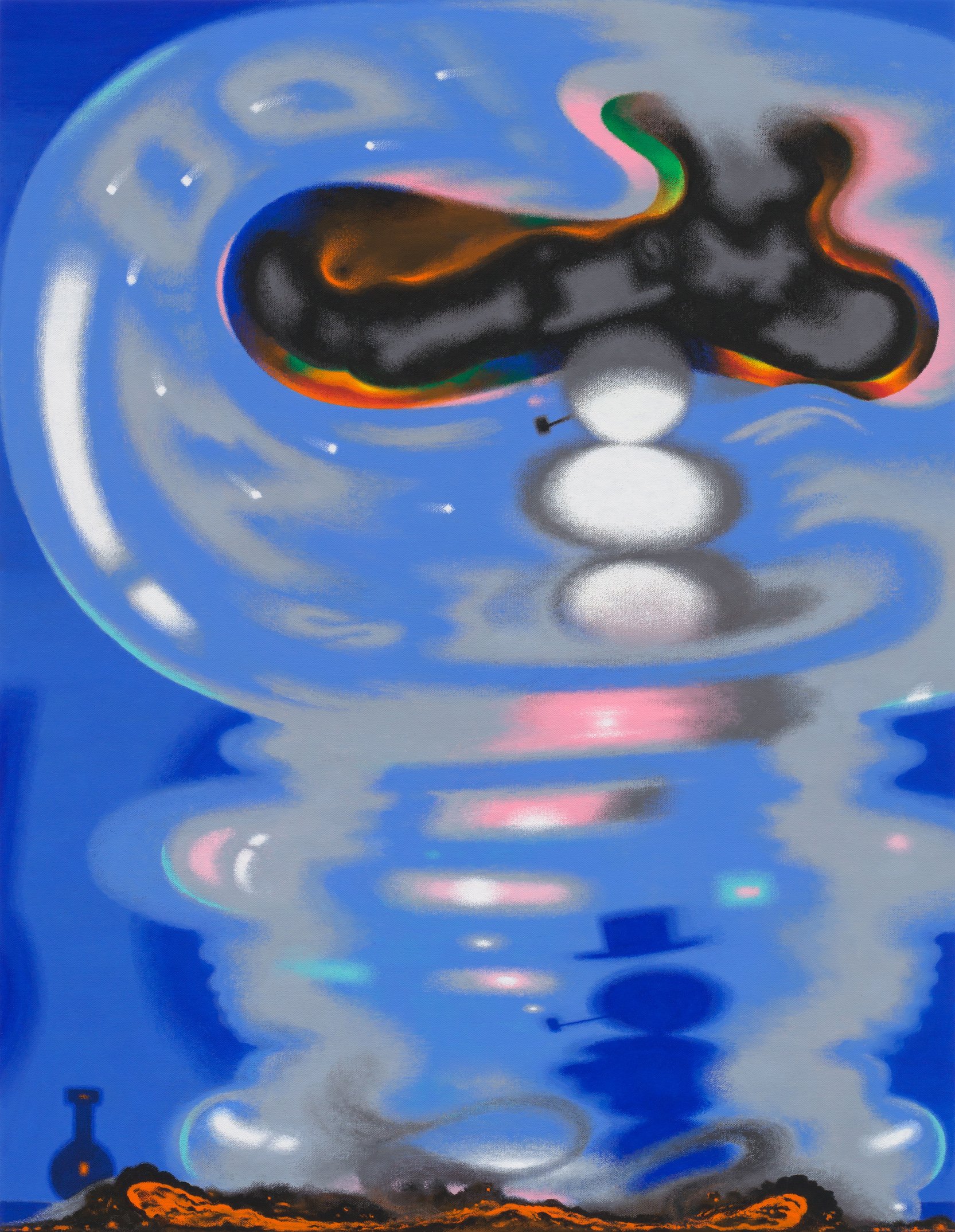

Peter Holm: Græsted, Denmark

It is one thing to set the stage for the emergence of new possibilities, but simply dwelling in a Thin Space is not the same as making good use of it. Again, the cornerstone of the original Celtic Thin Space was its permeability, a place for breaching seemingly impenetrable barriers, if only to reveal a brief glimpse of a more satisfying reality. But for most 21st century, non-Celtic artists, our longings run along different axes such as breaking through to the other side of creative dead ends or imbuing value and meaning to our artworks and to the hours we spend creating them. Of course, how these longings are actually realized depends on each artists’ constellation of temperament, skill, personal history, and, oh yes, whatever emotional hang ups they inevitably need to overcome. Sadly I cannot provide an instruction manual but only a call to action.

I turn now to a question that occasionally comes up with an artist friend when making the rounds of art galleries. This arises when viewing artworks that strike us as especially hollow, especially with a large number of them on display. One of us is bound to ask, “What exactly is motivating that artist to get into their studio in the morning?” Of course, there may be any number of motivations, but the point is to question what hoped-for payoff is driving someone to endure so much toil, perpetual non-recognition, and compromised balance sheets? Ok, so maybe the central draw is just getting away from doing the bills and house cleaning? Fine. Maybe it’s just the pleasure of making stuff that is aesthetically pleasing. Can’t argue with that. Maybe it’s a longing for higher status in the “art world.” I could go on. Indeed, these are perfectly good inducements for slipping into the studio, but to my mind they are not enough. Higher level, more profound creative experiences are also possible. There’s still money being left on the table.

Let’s face it, a meaningless, purposeless life sucks, but we each possess a different tolerance for drift. I believe that many artists share similar biographies as exceptionally sensitive people growing up in a predominately mercantile society. At a young age they probably developed a lower than average tolerance for meaninglessness and were a bit less sanguine about their life options on the menu. Probably starting in middle school, these kids were more likely to linger in the art, music, or theater classes, and to attach themselves to other “misfits.” Fast forwarding to their adult artistic selves, there is little reason to think these same needs are any less pressing.

So yes, Thin Space is just an ancient metaphor I am transposing onto the context of an artist studio. But metaphors can serve as more than literary devices; they can structure the way we make sense of things. For me, Thin Space is an empowering mental framework by which to feel and to think what was previously unfelt and unthinkable. What better way to pass the time in the studio?

I wish to thank the artists who so generously shared with me (and the readers) images of their studios. I was limited with how many images I could insert into the text, so the remaining images are displayed below. I can only hope that each of these artists are the lucky beneficiaries of their special “thin’ spaces.

Connie Goldman: Petaluma, California

Arvid Boecker: Heidelberg, Germany Donna Ruff: Little Haiti, Miami, Florida

Adrienne Moumin: Silver Spring, Maryland

Louise P. Sloan::Kings Point, New York Jaanika Peerna: Lisbon, Portugal

Ravenna Taylor: Lambertville, New Jersey

Beverly Rautenberg: Chicago, Illinois Camilla Fallon: Sharon, Connecticut

Midge Williams:Portland, Oregon

Seth Callander. New Haven, Connecticut

Yoella Razili: Los Angeles, California